With a rainy afternoon free in Manhattan (which is not something to take lightly, for anyone), I went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a trip I’d missed for at least a dozen years. It’s truly one of the world’s great art museums and I love being left free to gaze at art, looking for those pieces which may move me or thrill me in one way or another — through the heart or the head.

Starting in the Antiquities section, meandering among ancient Greek and Roman marble busts, torsos, and assorted objets d’art, there was no choice but to summon the spirit of the late, great Reynolds Price. As a naive 21-year-old at Duke, I’d stumbled into Price’s Milton class, with little idea that my life’s course was about to be shifted, dramatically. Later in that semester, after having shared social drinks at his country house and dined with him at a local Greek favorite, then cooked for him in his own kitchen with friends, I opened myself to the idea of being his full-time live-in assistant post graduation. An odd thought at first, it proved to be a wise commitment. Little time was required before I knew that there was truly no limit to the wisdom I could glean from the accomplished Southern Man of Letters. It proved more and more true. Sixteen years almost to the week afterI’d first called him “Professor Price,” the man I then knew simply as Reynolds breathed his last. Those later years were filled with frequent visits of afternoon drinks in his private living quarters, during which time we laughed heartily, told bawdy jokes, shared intimate stories, and continued developing what I regard as one of the deepest friendships of my life.

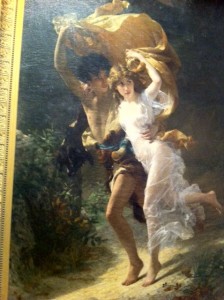

But back to the art! Reynolds possessed what was widely known to be one of the most eclectic, mature, and valuable collections of art — certainly in the state of North Carolina and likely this whole slice of the world. His house was jam-packed with everything from pop-culture icons to Picassos and Rembrandts, and many diverse pieces in between. [See video ‘Farewell to RP’s Art.’] Spending the year with him alone in his house meant: daily opportunities to learn about artistic movements and methods; being asked to reposition old works or hang for the first time newly acquired paintings; gazing at jaw-dropping landscapes and still-lifes by American masters while waiting for him to groom; intimately engaging with masterpieces in a way brief visits to a museum don’t allow. Without entirely conscious realization, my own sense of aesthetic appreciation was being developed in overdrive. Reynolds gave me a lesson in how to negotiate with a dealer on a visit to San Francisco and insisted on making the down-payment himself as a way to ensure I acquired the piece I truly loved — my first acquisition. He taught me ways to think about colors and composition, ways to comment on the energy of a piece without sounding pretentious. His love of art rendered a further dimension to his role as teacher of curious young souls.

So it was, walking through the Met alone, inspecting the contours and curves of the marble marvels, that I found myself summoning Reynolds’ deep baritone voice. We laughed privately to one another at the details or inaccuracies of some of the figure sculptures. I thanked him for allowing me to trace the deltoids of the figures on his shelves, of being able to connect with the marble in ways museums would never condone. I smiled, knowing that I knew why these torsos stood penisless, a simple fact most other patrons probably didn’t consider. I knew the textures of the cold stone statues from Reynolds’ private indulgences standing on his bookshelves and specially built supports. I thanked him, for those lessons were as deeply etched into my memory as the pelvic girdle of Hermes’ modest marble figure.

Reynolds’ joy at my continued engagement with art and aesthetics would have emanated effusively, were he physically present. He would have made jokes about Native American art which had escaped me or otherwise been inaccessible to lesser-read minds. He would have lingered silently with a piece for another few seconds, leaving me to wonder what was transpiring under that silver-white hair of his. He would have made a suggestion of a section of the museum which I’d dismissed otherwise.

In honor of Reynolds’ great contribution to joy in my own life, in the strains of art I’ve begun collecting, and in the myriad ways his love of visual media have changed my own life, I dedicated the 4.5 hour visit to the Met that afternoon to RP. I smiled, I gasped, I nodded. I allowed the power of simple urges and suggestions, brilliant compositions, and mysteries of art to wash over me. I tried to find new ways to encourage art to move me. I also did my fair share of people-watching, as Reynolds would’ve, attaching narratives to some of the situations and individuals. And I thanked him, through all of those meditations. Through these adorations, Reynolds Price truly lives on.

Thanks, old pal.